Time to step away from the AI hype and look at real costs for everyday AI use cases. This article focuses on internal tooling and operational spend, not so much more exciting user facing products; though the same cost dynamics apply.

My motivation here is I keep hearing AI will let teams “vibe code” their way out of SaaS, but AI can also turn the resulting products’ predictable Operating Expenses (OpEx) into volatile, usage-based costs. So I want to think through ongoing variable costs. Not ROI or quality risk, which matter too. Or the reality that AI talent may still be hard to find; just really more ongoing variables costs, which are different than our more predictable past tools.

Spoiler Alert: I’ll run through the thought process and offer up a spreadsheet. But the bottom line is this choice can be very business specific. Building your own with AI can easily spin up costs faster than you’d expect, as can burning tokens with SaaS solutions that add AI. But even speedier app development with AI assisted coding might cost you more than SaaS. Scroll down and just grab the spreadsheet or read on for all the details. It’s about more than just tokens vs. seats.

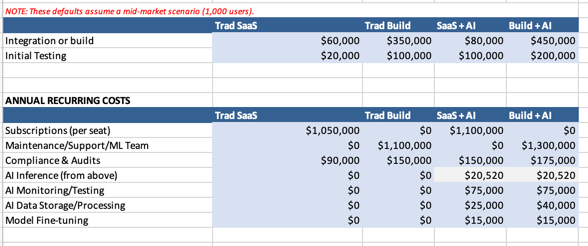

Quick Summary: SaaS often seems pricey per year, while “vibe coding” your own replacement can look cheaper early but gets expensive once you count labor, operations, and risk. The biggest drivers are seats, interaction complexity, and hidden costs like evals, testing, and ongoing auditability. DIY can win for small, short efforts, but at enterprise scale SaaS can still be cheaper on TCO even if the subscription line stings. In either case, for AI enabled products, there’s inference/token and other costs. Here’s the sheet if you’re skipping the rest of this article. (Note that older non-AI enabled build vs. buy examples are there just for historical reference and comparison.)

Also note that the cost assumptions I’ve put in here to start are radically higher than what simple token pricing might be compared to what you’ll find on a vendor’s chart. I’ve tried to add blended costs for things that reflect real production costs, like API costs, vector database queries for RAG, caching and so on. The point is for you to plug in your own numbers. If you want you can split out more granular costs to their own lines.

And, oh yes… don’t forget token costs are not the whole story. This piece is focused on costs, but when you shift to pricing and ROI, it’s worth reading John Rowell’s Context Is the Next Frontier in AI Economics.

Deep Dive

You’ve got the main points now. That was it. If you want to go deeper, here we go…

AI has captured our imaginations, and everyone’s trying new things. Maybe your junior designer can code a whole nuclear plant safety system over a weekend, or a dev lead can handle design because they can “vibe” the UX. Or maybe those are both still bad ideas. Even as these things get better every day, we don’t seem quite there yet. (Matt Shumer’s provocative post about AI progress notwithstanding.) When these things do work well though, they can offer real savings. Others will backfire and we’ve been seeing some of that. Either way, for everyday business apps, experimentation now has to answer the same question as anything else: does it help the business, either by growing revenue or reducing costs. The thing just released yesterday may be cool, but this is about whether what you’re building matters to the company’s longevity. Whether you’re embedding AI or building with it, the people funding these experiments will soon ask how the spend justifies itself next budget cycle. A vague “token allotment” line item won’t hold up for much longer.

Not every Product Manager owns a P&L, and many don’t focus on it until they’re more senior. Though I personally believe everyone benefits from understanding the business, not just their own product dashboard metrics. By the way, just as an aside if you ever want anyone in your shop to really feel the cost-benefit choices for customers, just have them shadow one of your top salespeople for a few days.

In any case, most PMs stay in feature-and-roadmap lanes while finance handles costs and that’s fine. But if you want to operate strategically, especially in mid-to-large companies, working closely with finance is non-negotiable because sometimes even seemingly “good” product metrics or associated KPIs don’t always move the bottom line. North Star metrics were, (and maybe still are), a thing for awhile. But you don’t have to dig deep at all to see there’s little nuance to such things. They can be not only just performative, but both opaque and potentially even incentivize bad long term choices. Now back to costs. In consulting, cost questions show up early and bluntly: what will it cost, how long will it take, what are the ongoing expenses? And maybe discussion around KPI outcomes, but not always. Depends on project. For simple delivery, it’s usually more around functionality. Outcome/KPI language shows up more in strategy or transformation work; pure delivery often defaults to “ship the thing” unless incentives are tied to outcomes. Spreadsheets help, but so do informed estimates. The obvious danger of spreadsheets and beautiful PowerPoints in human hands can be ironically similar to AI outputs: Confident and very precisely wrong. Either way, assumptions can be wrong, so the key is to make your best call, then update fast as reality shows up. For these new costs, it can be incredibly challenging as there’s not necessarily good baselines for either industry in general or your business in particular. At least not yet. Maybe we have some early case studies. Though I’ve known delivery managers with years of experience who can give reasonably accurate guesstimates with very few requirements.

In the meantime, CPOs, VPs of Product, and Principal PMs often share P&L responsibility with finance. That can include revenue targets, cost control, profitability forecasts, resource allocation, and overall business outcomes, not just feature delivery or user metrics. In product-led orgs, that accountability helps align product strategy with company goals and typically distinguishes senior product roles from mid-level or junior roles focused mainly on execution. (See Guide to P&L Management for Product Leads.)

As AI reshapes software, the classic “build vs. buy” question gets more complicated. What used to be a clearer trade between upfront Capital Expenditures (CapEx) for custom builds and predictable OpEx for SaaS now includes unpredictable variable costs from inference, heavier testing, and emerging liability risks. CloudZero even calls inferencing costs the margin killer. We’re going to re-visit P&L thinking through that lens, using CRM and support ticketing as examples to show how AI changes the trade-offs. (I picked those two as examples just because they’re such common and obvious use cases and have related features, even if different in purpose.)

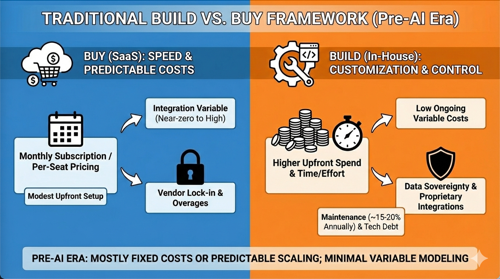

Quick Look At The Traditional Build vs. Buy Framework

Historically, the choice was simple: buy SaaS for speed and predictable costs, or build for customization and control. For common “workaday” needs, tools like Salesforce or Zendesk use per-seat pricing (say $50-$200/user/month as a range given there’s a variety of options) that budgets cleanly but can bring lock-in and overages. Upfront setup might be modest ($10K-$50K), though integration can range from near-zero to hundreds of thousands or even millions depending on systems and workflow complexity. Building in-house flips the profile: higher upfront spend (often $500K-$2M for a mid-sized app) driven by time, tools, and engineering effort, regardless of how it’s accounted for. I’ve personally led selection and stand up of CRMs at a few different companies and spent either zero dollars or tens or hundreds of thousands on integration. The costs depend on your context and complexity.

After launch, with SaaS variable costs are usually low and the investment is spread over years, with maintenance often around 15-20% of build cost annually. Or somewhere around there. With AI thoguh, See: The True Cost of Implementing AI in Business in 2026 for more line items you may want to add to your model. The build approach may fit when regulatory issues, proprietary integrations or data sovereignty really matter, but it slows time-to-market and creates tech debt. It also used to be the default for highly regulated or security-sensitive software. However, over time, cloud providers layered on compliance for industries from healthcare to government and more. Now though, both options likely include some kind of token burn.

These models worked in the pre-AI era because costs were mostly fixed or scaled predictably. There were always “known unknowns” like downtime, or regulatory surprises, but most teams didn’t model them unless the system was truly mission-critical. Maybe because such issues were mitigated by SLAs or were insurable. AI changes this. It’s a core shift in economics. Inference turns what used to be negligible marginal cost into a real variable (say $0.02-$2 per interaction), and testing expands beyond functional QA to robustness against hallucinations and bias, potentially adding 20-50% to dev budgets. Liability risk can rise too, as AI mistakes create new legal and insurance gaps. Even when model pricing looks cheap, for example, Google Cloud’s 2025 pricing documentation list enterprise chatbot inference around $0.0375 per million input characters (as of Feb 9, 2026), though Google Vertex AI pricing is token-based, not character-based (characters roughly convert to tokens at ~4 chars/token). Current rates for Gemini 1.5 Flash (common for chatbots) are $0.08/1M input tokens and $0.30/1M output, or ~$0.38 total per 1M blended. This is a snapshot I looked at while writing this. It’s probably already wrong. CloudZero’s analysis reveals the true per-workflow cost can be 10-50x higher once you include vector search, memory, and moderation, turning a $0.01 call into roughly $0.40-$0.70. These are just examples. Clearly, you have to re-check whatever option your considering today. And re-check tomorrow. This is part of the challenge.

The AI Factor: New Layers of Cost and Risk

AI doesn’t just speed up builds. It’s not that simple. It can reshape P&L. Using APIs can cut dev time, but ongoing inference creates “pay-per-thought” economics where spend spikes with usage, unlike flat SaaS fees or low-marginal-cost internal builds. In high-volume apps, costs can swing wildly between simple tasks and complex ones. 2x or 5x is perhaps manageable, but what if it’s 100x, and you only discover that after shipping? For example, a support system handling 10,000 monthly queries at 2,000 tokens each on Claude Sonnet pricing around $3 per million tokens would cost about $60/month in raw inference, but multi-turn workflows or document-heavy tasks can push that 10x higher. That might still be a bargain, the point is to pay attention to fast const inflation.

Testing gets harder too. Traditional QA hunts deterministic bugs; whereas AI requires probabilistic evaluation, stress tests for edge cases, and defenses against things like data poisoning, ideally using detailed rubrics and sometimes third-party tooling or audits. There’s a real “quality tax” emerging for AI systems. Check out the article The 2026 Quality Tax.

Liability also suggests more P&L scrutiny. Enterprise AI hallucinations can drive bad decisions, while vendors can cap exposure and shift blame to customers, and insurers remain wary of covering AI-specific failures. That means teams may need reserves for legal and operational fallout and tighter governance modeled with finance and legal. When the lawyers get nervous, it’s maybe worth slowing down and thinking. See: AI Hallucination Liability in Product Design, Insurers Uneasy About Covering Corporate AI Risks, AI Vendor Liability Squeeze. Again, these things may be getting better everyday and be even more magical a couple of years from now. At the same time while you read all the hypey goodness right next to the fear everywhere, doesn’t it maybe say something that lawyer’s are scrambling to try to carve out liability? It might be a temporary “mitigate an unknown response” from a group of folks who’s jobs it is to protect against risks. Still, to me that’s a signal. Just what it says or how severe? Not sure yet. Due diligence aside, does anyone doubt that more folks have a Launch First, Ask Questions Later attitude these days? Even with decent diligence, some risks in these spaces might just not be learnable until products are out in the wild. This is opinion on my part, but even the best test evals and rubrics probably can’t catch everything in testing.

Example 1: CRM Systems – Seats to Smart Agents

CRMs like Salesforce show how SaaS spend scales with seats (e.g., $150/user/month x 1,000 users ≈ $1.8M/year, though pricing varies due to optional plans.). Buying avoids a $500K-$2M build, but it doesn’t eliminate customization. Integrators can heavily reshape the platform, often because you need them to.

AI changes the picture again. Adding agents for lead scoring or email automation or whatever else introduces variable inference (e.g., at $0.03/1K tokens, 10K daily interactions could be roughly past $100K-$500K/year, depending on complexity of the actual query and associated tokens used). An AI-native CRM might ship faster but needs tougher testing for bias and reliability, potentially adding ~30% to dev cost, plus governance like human-in-the-loop. And if decisions are contested internally or legally you’ll need observability and audit trails, not “the model said so.” There’s another issue of quality and customer loss as well. I haven’t been able to find data about this yet, but just ask yourself, “Has your customer service experience been getting better or worse?” I think a lot of this stuff not only doesn’t work so well yet, but is bad enough that it could easily turn customers off. Maybe this will all get a lot better fast. For now though, there’s even a couple of companies I’ve noticed push real human customer service in their advertising. I’m just going to assume there’s a reason for that. So you may want to double down on that testing aspect of things.

Example 2: Customer Support Ticketing, Scaling Chatbots

Ticketing SaaS might run around $49/user/month, offering predictable scaling for large teams. Let’s say a traditional internal build can cost $300K-$1M upfront, with relatively low variable cost for high-volume usage.

Add AI and the economics shift: agentic bots can handle tickets, but inference for 10K monthly interactions might add $50K-$300K/year in variable spend. And that ignores the real-world cost of bad experiences already mentioned. Like those circular, “won’t let you out” support loops we’ve all felt lately. Testing also expands to include prompt-injection defenses and output validation, stretching timelines, while liability grows if bots give harmful or incorrect advice and vendors disclaim responsibility, leaving enterprises holding the risk. This gets back to metrics. Great, you radically decreased CSR costs and time to handle. Are you sure you’re not negatively impacting churn? Lifetime Value (LTV) is a lagging indicator. If you get to where some lever is messing with that, you may have a hard problem to undo.

Designing a Spreadsheet for High-Level Analysis

To make this practical, PMs and finance teams can use a simple Excel/Sheets template to compare 3-5 year TCO across options. I’m going to share one, though it won’t match every situation out of the box.

Huge disclaimer: this isn’t a full P&L or ROI model. It’s just a rough cost ballpark you can feed into those. The default ranges are experience-based guesses and will be wrong for your context, so use your own numbers and treat this as a starting point. I also didn’t include NPV, full sensitivity analysis, or wide variation for storage and RAG databases; add those as needed. If you come up with something better or more complete, just share it back and I’ll update mine. As mentioned earlier, I’ll repeat: Note that the cost assumptions are radically higher than what simple token pricing might be than you’ll find on a vendor’s chart. I’ve tried to add blended costs for things that reflect real production costs, like API costs, vector database queries for RAG, caching and so on. The point is for you to plug in your own numbers.

OK, that should just about cover the disclaimer. I’ve worked on a wide variety of consulting projects over the past handful of years and these seem like generally in the ballpark ranges. But scope can of course vary tremendously. And inferencing / token costs change practically daily. If you like, check out Cloudidr’s Complete LLM Pricing Comparison 2026: We Analyzed 60+ Models So You Don’t Have To.

In any case, if you find errors or have other issues with the sheet, let me know. Here’s where you can get it:

When estimating token costs, the “right” number depends on provider, model tier, and whether you’re paying for input or output tokens. Pricing is usually per million tokens, but it’s often easier to reason about per thousand; output can cost 4-8x more than input, and caching and non-text objects can change the math. Prompts with lots of context can mean high input with short output, while “expand this into a report” flips the ratio, though over time, accumulated conversation history can make input dwarf output even when each new prompt is small.

So treat this spreadsheet as a rough first draft you’ll need to adapt. The non-AI build lines are there mainly to anchor you in familiar fixed vs. variable costs before shifting to AI’s more volatile profile. The tricky part in AI build-vs-buy is that inference economics keep moving: historically SaaS often wins except at very high volumes, but with AI the breakpoints are less clear, and “in-house” usually still means cloud, just with different choices about hosting models vs. paying providers.

Conclusion: Strategic Costing in an AI World

AI is blurring build vs. buy for business apps. It wasn’t ever simple, but it was simpler; now leaders have to model inference volatility, heavier testing, and liability alongside the usual cost questions. Use the spreadsheet and a couple scenarios (CRM and ticketing are just common examples) to make informed choices, and work closely with finance, because the gee-whiz phase of AI experimentation is colliding with budget reality. The models are still about fixed and variable costs; it’s just that AI can add a lot more variability, which makes pricing and planning harder. Token deflation does typically occur over time, so ideally costs keep coming down. And yes, if implemented well, headcount costs may also decrease. In the end an increase in variable costs may be tolerable for the case at hand. Still, it’s not just a “tokens vs. seats” comparison if the SaaS solution also is using variable AI costs.

How are you dealing with all of this? Share with the group.

See Also…

Quick note on using other estimators: These are usually for one-shot comparisons. Very few model usage over time. People will typically find more use cases or use more multi-turn sessions as they get more comfortable or sophisticated.

- Cost Estimation of AI Workloads (Great Article.)

- Observations About LLM Inference Pricing

- AI build versus buy: How to choose the right strategy for your business

- LLMs API price calculator

- Another LLM Pricing Calculator

- One more LLM pricing calculator

- JumpCloud TCO Calculator (Warning: this is a direct link is to an Excel file.)

- There’s more of these. But these few are enough to get a sense of model comparison, AFTER you try to determine which models best satisfy the needs at hand.