We all have a choice about how we use these new tools. And if you are a parent, how you teach your kids to use them. If you lead a team, the same questions apply. How should your business use them, and where do they add value for your people and customers?

This is an exploration of the “why” behind a lot of what is going on. I reference behavioral research along the way.

This will not be “Here’s how you build a chatbot to take over the world tomorrow.” Or “this will replace your workforce tomorrow.” It is also not a “Here’s what you should do checklist,” though there are practical ideas near the end. Think of it as a tour of how AI can shape how we live, work, and think, with background on how it works and perspectives you may want to consider for yourself, your teams, and family. The topics are not new, and not all original. The goal is to revisit common themes and add depth by getting closer to their primary drivers. Not just what to think, but why the assertions may be true.

Note: this is a long form article, not the usual LinkedIn bullet points. Some articles get built in bits and pieces over several years as I learn about a topic They’re really my research notes. I usually include a quick summary up top. Not this time. This one is for deep background and context. I think these issues matter for the next set of our collective societal decisions. If you want a “what can I do right now” checklist, this isn’t it.

A Foreword on Our Hype Cycle First

I will get to the main points in a moment. First, it is worth naming the clickbait festival of prognostications. We need to level set. Let’s take a breath and look at the hype cycle calmly.

This tech is diffusing fast, but the usual cycle still applies. It has been decades in the making, and Google’s 2017 “Attention Is All You Need” paper was a major trigger by popularizing the Transformer architecture behind modern large language models. (Another backgrounder on Transformers.) This is what most people now mean by “AI.” Yes, disruption is here. You’ve seen the headlines. But the more interesting impacts may be second and third-order effects that show up as people change behavior and systems reorganize. Think about autonomous vehicles. If they become ubiquitous, do we still need as many traffic lights or street signs? Maybe. Maybe not. Though we might enjoy lunch delivery via drone direct to our cars. What will deeper cascades look like? It might not be mass unemployment. It could be the opposite, a boom in small, bespoke businesses that were never economical before. Not every future is dystopian, and even “fast” rarely means overnight.

The “jobpocalypse” crowd seems to say every career is disappearing in months. Yet there is evidence that “replace the whole corporate system in a weekend with one vibe coder” is not working reliably.

Yes, Sam Altman and Matt Shumer say capabilities improve daily. Shumer claims the “getting better vs. hitting a wall” debate is over, though critics counter that reliability trails the hype. Shumer’s “Something Big Is Happening” post went viral, but see Gary Marcus’ response for balance: “About that Matt Shumer post that has nearly 50 million views” From my experimenting, I can see both sides. It’s a useful discussion, but no clarity yet.

So I agree with the direction of travel, but change takes time. Plenty of large companies do fine even as decades-old “Digital Transformations” remain a grind. Many businesses and personal activities will not care about any of this. Most will land somewhere in the middle of the adoption curve. During this time, what should some of us be thinking about? Education, sure. Personal experimentation, yes. Leveling up usage in your core field, absolutely.

There’s something else though. Maybe consider protecting your brain along the way. If second and third-order effects matter, one set of effects may include:

- Actual degradation of thought.

- Poor decisions based on a false sense of success after getting an easy answer.

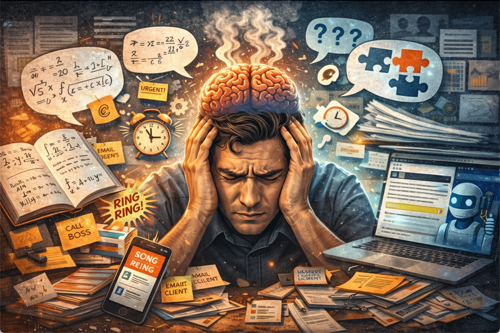

- Anxiety from legitimate concerns, imagined futures, and the feeling of falling behind.

So what should you consider right now about your brain, your kids’ brains, and your team’s brains? This has been written about recently, but I want to go deeper into the background.

What is Cognitive Load?

Cognitive load is a simple idea with deep implications. Your working memory is limited. Learning and reasoning suffer when we overload it. Cognitive Load Theory is most associated with John Sweller and research on how instructional design and problem-solving can consume mental bandwidth that would otherwise form durable understanding, or schemas.

Common framings distinguishes three types of load:

- Intrinsic: the thing’s inherent complexity (calculus vs. basic arithmetic).

- Extraneous: unnecessary burden from poor presentation, noise, or confusing tools.

- Germane: the “good effort” that builds understanding. Organizing knowledge, retrieval practice, refining models. More on Cognitive Load theory. (Pay attention. This is the subtle one.)

AI can reduce extraneous load dramatically through summaries, first drafts, and quick explanations. But it can also quietly reduce germane load if we let it do the thinking while we only approve the output. Think of the old line: “give someone a fish and feed them for a day, teach them to fish and feed them for life.” For many tasks we do not need deep mastery, so “just give me the answer” is fine. But if you are reading this far, you are probably the curious sort. My kind of people.

A popular concern lately is cognitive offloading and how it can erode our ability to think. The reality is we have been doing this for years with assistive tech, just to a lesser degree, often with obvious net benefits.

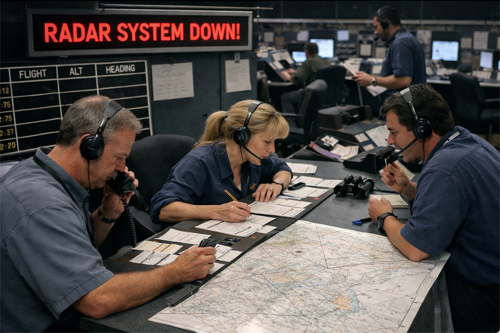

Aviation is a clear example. Cockpit automation can ease pilot load and improve safety, but it can also reduce situational awareness. We don’t have to look far for tragedies. (Asiana Airlines Flight 214, San Francisco, July 6, 2013, Air France Flight 447, June 1, 2009). Fortunately, this level of tragic outcome is rare, and the safety gains generally outweigh the risks. Personally, as a general aviation pilot trained on “steam gauges” and now flying behind glass cockpit avionics, I’ve seen both worlds. I can’t know what it’s like to learn only on the new systems, but I suspect I’d feel less aware without the old-school foundation. Actually worse. I wouldn’t feel it because I wouldn’t know any better. There’s a real difference between manually navigating with charts, radio beacons, and magnetic headings versus following the magenta line. The latter frees bandwidth to monitor systems and manage situations, and – I believe – it’s safer. You just may not be quite as “on it” as when you do more manually.

So how do we choose the right depth of engagement now, across all the places we can offload tasks, physical and intellectual? Especially when offloading becomes mundane and habitual. Even deeper, how do we notice we are making a choice at all? Where is the switch to change modes when we need to? I once watched a fast food restaurant keep operating when the registers failed. This was back when most people carried cash, so payment was not the blocker it might be today. One person walked the lines with a notepad, taking orders doing bills by hand. When she took our order I said, “wow, they really left you on your own out here!” She leaned towards me and whispered, “I’m the only one who can do math.”

Load Shedding

Look at our car GPS maps. They’re great for efficiency, but people often lose “cognitive maps” (route planning, landmarking, spatial memory) and get worse at recovery when the system is wrong or unavailable. (See: Habitual use of GPS negatively impacts spatial memory) I heard a story about an Uber driver who’s phone glitched. The passenger said he seemed completely lost, both geographically and emotionally, until it came back.

Consider medical clinical decision support. It can improve safety and consistency, but risks turning care into “checkbox medicine.” Examples are endless. Consider distracted driving. I do community volunteer work with a fire/rescue service and have been an EMT for decades. I’ve responded to several crashes caused by cell phone use. It’s cognitive overhead and bad task switching.

So far, most assistive tools have been purpose-built and scoped (aviation, traffic, facilities management). Users in narrow fields were trained on use and failure modes. Air traffic controllers can revert to non-radar procedures in some contexts, at reduced capacity, thanks to recurrent practice. Now we have general, powerful tools used by everyone. Liberating for many, potentially debilitating for others, often in insidious ways. We lack broad awareness of what is mission or safety critical, procedures for when things fail, recognition that failure occurred, or even what “wrong” looks like.

This is opinion, but I think early signals are already in. We are not ready. More precisely, a lot of people may not do well. Which cohorts thrive versus suffer? We don’t know yet. But asking where the risks show up, and in what contexts, seems like the right approach. Context is everything. This looks similar to past cognitive offloading, but it’s a step-change in magnitude. People are already reporting problems with remembering what was done, why it was done, and how to recover when the assistant is wrong or unavailable.

A Subtle Trap: Fluent Answers, False Confidence

A confident and seemingly competent answer can create a false sense of security. You feel you understand because the response is coherent, even if it is wrong. That gap shows up when stakes are higher, constraints shift, or something breaks and you cannot get back to safety.

You’ve likely heard when AIs miss it’s called hallucination. This label is misleading. It’s an example where a bad label became a meme. (See: Large Language Models Don’t “Hallucinate”, and What are AI chatbots actually doing when they ‘hallucinate’?) The reason it’s a problem isn’t just output might be wrong, or nonsensical regardless of sounding okay. It’s that answers can seem plausible over judgment thresholds because we’re not paying attention. Ironically part of the reason for this might be that these things are really good most of the time! And we may be likely to defer to such things because it’s a machine. We think it’s less fallible than humans.

We have little experience with machines that are kind of right, but not really. We have that with each other; with people. We’ll often trust experts even when they may be off. We also use a variety of signals to assess. It seems we suspend this judgment with machines though. See: Algorithm appreciation: People prefer algorithmic to human judgment. This automation bias and ‘algorithm appreciation’ suggests people can overweight machine-generated answers, especially when outputs are fluent and confident, sometimes reducing vigilance and error-detection.

There’s a related risk called “cognitive surrender.” In a 2026 working paper, researchers propose a “Tri-System” view of reasoning where, alongside fast intuition and deliberate thought, we add a third system, “artificial cognition,” that operates outside the brain. There’s a pattern: when participants had access to an AI assistant, they used it on most trials, and their accuracy rose sharply when the AI was correct but fell when it was wrong, while confidence still increased. People often stop constructing an answer for themselves and instead adopt an AI-generated answer as their own, even when that answer is flawed. See: Thinking—Fast, Slow, and Artificial: How AI is Reshaping Human Reasoning and the Rise of Cognitive Surrender. I recommend earlier works by Daniel Kahneman, like Thinking Fast and Slow. This makes sense for some obvious reasons. When do we stop looking for something? Well, that would be when we think we’ve found it.

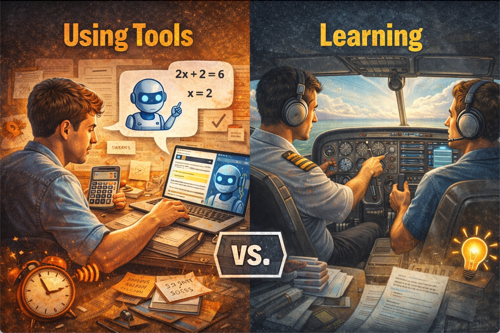

What About Context: Using a Tool vs. Learning

For learning, the key distinction is this… AI can help you perform, but performance is not the same as learning. Learning is a change in what you can reliably do later, under variation, without support. I can sit in a pilot seat and move the controls with constant instructor input, but that does not mean I’ve learned to fly, unless I’m also staying actively mentally engaged.

If you use AI like a calculator while learning arithmetic, you can finish homework faster and still never build the mental muscle the homework was meant to build. I’m not saying don’t use calculators. It means use tools intentionally, and sometimes do things manually so the capability becomes yours, or at least enough to build intuition. Does someone casually reading a P&L see what a CFO sees? If you look at clouds, do you see a bunny rabbit? Great. Now what would a pilot see? Or a farmer? Or a meteorologist? Or a roofer? Depth of skill, and probably creativity, comes from intuition built through deeply internalized lessons, not shallow surface knowledge. The best combination? My opinion? Deep mastery coupled with a beginner’s openness. Maintenance of child-like wonder with experience. Ironically perhaps, AI tools can likely help hone efforts to level up if used properly. Yet just as surely drive towards mediocrity or less if not.

Some think this no longer matters in an age of ubiquitous AI, even ignoring what happens when the power goes out or a cell phone dies and some become practically paralyzed. But I’m talking about “expert sense,” that ineffable context built through both repetition and working through many scenarios over time. Some believe AI can have it because it has so much information. Others argue it’s “just” sophisticated auto-correct supercharged by linear algebra. Then we hear, “agents and reasoning and tools will fix it.” Perhaps. Still, do these systems have “that special thing?” And does it matter anymore? What if they’re faced with the new? Will just chunking through all the probabilistic outcomes and maybe a touch of goal-seeking strategy cut it?

A colleague of mine, Lori-Ellen Pisani, PhD, says that “learning is inseparable from human/relational conditions, and that what many systems label as “social-emotional learning” (SEL) is best understood as developmental capacities that shape how academic learning happens.” She further says with regard to literacy in particular, “literacy inherently exercises perspective-taking, meaning-making, discussion norms, revision, and reflective thinking.”

Does that mean we can’t learn from AI? Of course not. People use these tools to learn every day, intentionally and through transference. Still, if SEL is critical in classroom conditions, it seems fair to ask whether emotional context matters in any learning state. So what is that state when operating with AI? We know people, and kids in particular, can form an emotional and even empathetic relationship with these tools.

Add one more layer. Low-risk vs. high-risk environments. For Low-risk, (brainstorming, drafts, exploring topics), AI accelerates beautifully if you treat it as a tutor and stay engaged. High-risk, (medical, legal, financial, production), AI turns into a liability the moment it lulls you into “auto-accept mode.”

In aviation, I’ve mentioned the “follow the magenta line” as a phenomenon: pilots can become over-reliant on automation’s clean path and lose situational awareness when reality diverges. The right response isn’t “ban the magenta line.” It’s training, procedures, and a mindset, automation helps until it hurts, and you must retain the ability to take over.

A similar pattern is emerging in knowledge work. AI can write code you can “follow the syntax” of, but comprehension is different. It’s knowing how the pieces connect, what breaks when you change something, and where the landmines are. If AI shifts your work from building to mostly reviewing, you may gain speed now, but at the cost of deeper understanding later.

This is why educators and assessment designers are starting to worry about the “false positive problem”. Work products can look impressive while underlying understanding lags. Recent OECD-linked coverage has used the phrase “metacognitive laziness” to describe the risk that students offload the thinking-about-thinking part, the planning, monitoring, and reflection that makes learning real.

So what do you do? Here are practical moves you can take yourself, and encourage in your kids, colleagues, and teams. Just keep in mind I have zero professional credentials in this. I found much of it through research, sometimes with AI. You probably should not listen to me. I’m shocked you’re still here. But if you want suggestions, here they are.

- Use AI to explain things, then verify. Treat the model like a smart intern or assistant that can summarize quickly, but does not know when something should not work that way. Verification can be as simple as checking primary sources, running a quick test, comparing two approaches, or asking the model to show its assumptions and edge cases.

- Convert answers into reps. When you use AI to learn, turn the output into practice: explain it back in your own words, do a few problems cold, write the outline without help, debug without the assistant, or teach it to someone else. The point is to move from “I saw it” to “I can do it.”

- Make “why” mandatory, not optional. If you find yourself accepting an answer without being able to explain why it’s correct, pause. Ask, “What would have to be true for this to work?” and “What would break this?” Encourage others to do the same. This single habit fights the false sense of competence.

- Use AI as a second brain, not a replacement brain. Offload reminders, formatting, drafts, and retrieval. Keep judgment, interpretation, and risk decisions in human hands. If you are using it for a high-stakes choice, treat AI as one input, not the decision-maker.

- Deliberately practice without it sometimes. Create “no-assist reps” the way athletes train without supports. In coding, write small pieces from scratch. In writing, draft a paragraph before asking for alternatives. In analysis, sketch your conclusion before asking for critique. If you’re working with others, encourage your team to do the same, especially juniors who are still forming core mental models.

- Build a personal checklist for high-risk situations. For anything high stakes, adopt a short routine: “What is the claim? What is the source? What is the test? What is the failure mode? What is the rollback?” If you are leading others, make this cultural.

- In teams, don’t just measure output volume. Measure error rates, rework, recoverability, and how often “someone actually understands the system.” If AI is truly helping, quality and resilience should improve, not just throughput. Make it normal to ask, “Who can explain this end to end?” and ensure there is always a human who can.

- Reward good skepticism. If you want others to use AI well, praise the behavior you actually want, people who double-check, who admit uncertainty, who surface assumptions, and who slow down appropriately. Otherwise, you will get faster output and weaker thinking.

Nothing I just listed covers autonomous systems that act on their own. That’s its own large and evolving body of knowledge. Whether it’s an autonomous weapons system or your new AI snowblower, the trust and decision-making questions are different.

Too Close vs. Too Far from the Problem

In discussing business strategy, Alex M.H. Smith talks about where great strategy ideas come from and lands on people and personality. He argues it’s really about Creativity, Courage, and Charisma. Does AI have any of these? Some might argue creativity, even if it’s probabilistic or accidental. There are even settings for that. But do these tools really have those traits? Not yet. Still, maybe they can get us to 90%. Maybe being at 90% is fine most of the time, and having so much knowledge, even if probabilistically regurgitated, solves most day-to-day problems.

It’s that 10% though. Maybe less. Isn’t that where humanity has often surged? Of the billions of people on the planet, it’s that occasional one of us that has the breakthrough.

So here’s the real question. Will the intellectual degradation that’s all but unquestionably going to grow with AI turn that 10% into even less. Or 1% or whatever it is. This isn’t an academic science paper. I have no data here. It’s just a thought experiment. If a great many of folks who otherwise might have exercised their brains in new ways concede more of them to AI tools, what might we collectively miss as a society? As a species?

This is where AI expert Sol Rashidi’s framing lands as a blunt warning label. She coined the term “Intellectual Atrophy™” to describe what happens when convenience becomes dependence, when we repeatedly outsource critical thinking, common sense, and creativity until those skills weaken from disuse.

A useful way to apply that lens without going full doomsday attitude is to consider distance from the problem.

- Too close: you’re grinding without leverage, drowning in extraneous load. AI helps give you a wider view.

- Too far: you’re approving outputs you can’t evaluate or just being too lazy to think through, and your role becomes “rubber stamp.” AI hurts by eroding the very competence needed for judgment.

- The middle: Goldilocks territory. Use AI to compress the tedious parts, but stay close enough that you could still do the work if the tool disappeared tomorrow, even if it would take longer. That’s harder. You have to stay an active participant, still a driver, not just a passenger. This may be especially tough when the pressure is to automate everything. Maybe the compromise is to automate mostly the tedious and use the classic 3 D’s as a filter: the Dangerous, Dirty, and Dull.

We can treat Rashidi’s “Intellectual Atrophy™” as a warning label. The “cognitive surrender” paper offers a mechanism for how it can happen in day-to-day reasoning; repeated deference to System 3, especially when we cannot judge whether it’s right. But we defer all the time, like when we hire an electrician, trust a doctor to read an MRI, or ask a programmer for help. So what’s different here? Is it that we want a real person to blame for bad outcomes? That we have more signals to assess humans? That we distrust systems with nothing to lose? AIs probably don’t care about reputation. Do they? Maybe a good expert shows calibrated uncertainty and knows boundaries. Software has no fear, shame, or downside.

The Largest Challenge?

Want to know one of the biggest challenges? Here it is. I hate saying it because I’m generally up on the future. I don’t care much for cynical outlooks. Sarcasm? Sure. Obviously a big fan. But when it gets real? I prefer optimism.

Except here? I think I’ve been sensing this happen a lot more. And it’s this. Mostly people just do not give even a little s$#$ about consequences any more. Not really. They want to ship fast and just assume or try to insure away risk. Or maybe they do care, but they’re more afraid of missing out. The vibe is “second place just means you’re the first loser,” and ethics and governance take time. That pressure has been building for years. Yes, some teams check boxes in press releases, but across tech, the mantra is still execution and speed. Ship. Iterate. Call it “efficiency” if you want. Either way, more garbage gets tossed out to see what sticks.

Over time, more thoughtful teams may prevail. (Or the lawyers will help with some expensive consequences.) We’re already seeing more calls for observability and auditability. If customers truly value those, incentives can shift. Still, we’ll have to contend with a larger raft of garbage than ever before. Business has always flirted with regulatory edges, and we’ve seen what happens when lines are blatantly crossed into criminality. The harder part now is that the harm can be subtle. Like medicine, many tools can heal or hurt. Knives are among humanity’s earliest tools, and also weapons.

How does this relate to AI? It’s land-grab time. We’re still early, and everyone assumes there will be a few big winners and a lot of also-rans. Google ruled for decades and is still in the game. Money is still chasing development, market expansion, and share. Profitability concerns are rising, but the rush continues. And that’s before we factor in forces tied to national interests.

Meanwhile, many players are burning cash and their business models remain a concern. Talk about AI ethics all you want, and watch all the presentations you want, but how much was truly resolved before launch? Not much beyond a few obvious guardrails. Yes, some learning only happens at scale, and you can’t fix what you can’t see yet. But the reality is that if you take time to do the hard pre-work, you risk being late, or at least being seen as late. And it’s telling that some fundamental failures have come from top companies with legal teams larger than whole startups, not just scrappy startups who maybe have never heard the term GRC.

Am I being too harsh? Not if you see the pattern in recent news. Google paused Gemini’s image generation of people after high-profile historical and bias failures. OpenAI paused a flagship voice after a consent and likeness controversy. Google’s AI Overviews shipped, then viral wrong answers forced rapid public corrections. Multiple generative AI companies are now fighting copyright and provenance battles in court, suggesting that big “ethics” questions were not settled before scale. In a land grab, the incentive is to ship first and patch later, because pausing can feel like falling behind, probably because you are. And in fairness, some issues only show up at scale, even with careful evals. Someone on LinkedIn talking about speed to market actually said this, “The security will get fixed. The head start won’t.” He might just as well have been talking about any quality and ethics issues. At least he was blatantly honest in saying it out loud. Should there be any wonder why we’re going to face some major failures?

Add to this that security and privacy issues have been negative externalities for decades. This hasn’t changed. The consequences, however, may have just become more severe; both episodic and systemic.

You know how I said I don’t like being cynical about the future? I still don’t. I’ll also admit I was never a fan of regulation, or Governance, Risk and Compliance (GRC), unless it was for safety-critical domains like medicine, where GRC is arguably part of the product. But I’m coming around. We barely understand these tools, they evolve faster than we can learn them, and we do not have the philosophical maturity to match the speed. That’s a problem. Maybe the problem.

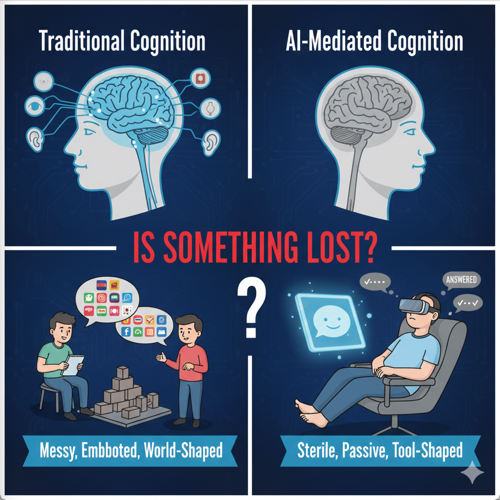

Maybe There’s More to Cognition than Brains

One reason this whole conversation gets tricky is that we often talk as if cognition is something that happens only inside the skull, as if your brain is a CPU, your senses are input devices, and your hands are output peripherals.

But a lot of modern thinking about cognition points to something messier and more human. Cognition is shaped by context, and context is not just information. It’s environment, relationships, language, culture, tools, and physical constraints, all the stuff we’re embedded in.

Andrew Hinton’s work is useful here because he treats context as a structure; layers of constraints and cues that shape what things mean, what actions are possible, and what choices feel “obvious.” In Understanding Context: Environment, Language, and Information Architecture, he argues that design doesn’t merely respond to context, it participates in creating it. (As I write this, I’m only 1/3 through this book right now, but can already recommend it!)

Now bring that into the AI era. If you work primarily through a chatbot, the chatbot becomes part of your cognitive environment. If your kid learns primarily through an assistant, that assistant becomes part of their learning context. If your team “thinks” through a tool, the tool shapes the norms of reasoning; what gets questioned, what gets verified, and what gets skipped.

This is where embodiment matters. Not in a mystical way, but in the practical reality that humans learn and reason through doing, gestures, writing, sketching, speaking, moving, building, arguing, revising, noticing confusion, and recovering from error. If a tool removes too much friction, it can remove the sensations that tell you, “I don’t understand this yet.” We used to call the hard part “paying your dues.” But who wants that if it’s avoidable?

That’s a provocative way to reinterpret the risk: the worst-case outcome isn’t that AI makes us “dumber” overnight. It’s that it reshapes our context so that we do fewer of the embodied behaviors that generate insight, fewer reps, fewer struggles, fewer mistakes we can feel and correct. In that sense, cognition is not just what the brain computes. It’s what the whole human does in a world of constraints.

That suggests a practical design principle for life and organizations. Don’t only ask what AI can produce. Ask what kind of humans its use patterns are producing. I’m not sure we’ve ever had to be this explicit. We have a more sophisticated view of instructional design than we used to, and we’ve long known exposure shapes learning and behavior. The difference now is that these tools may become ambient and subtle at the same time. We may need to be deliberate in how we manage them. If we sleepwalk through it, we might not like where we wake up.

Conclusion: The Point Isn’t to Use AI Less. It’s to Use It Deliberately.

This isn’t a call to reject AI. It’s a call to use it with intention, and teach ourselves, our employees if we’re business leaders, and our kids if we’re parents, how to think about these tools. So far we’ve handed out extreme power tools with no instruction manual or warning labels. With a chainsaw or blowtorch, most people would pause and think, “I should be careful.” With AI, not so much. I have no illusions. Most will take the easy way. But I think the future will belong to those who can wield these tools well and still retain a sense of themselves while doing it. Maybe that’s always been true. Those who use their tools better do best, whether a paintbrush, a power drill, a spreadsheet, or an AI copilot.

AI is already one of the most powerful extraneous-load reducers we’ve ever had. It can summarize, draft, translate, brainstorm, and tutor. It can give overwhelmed people leverage. It can help teams move faster. In many contexts, it’s a genuine gift.

But if we confuse fluent output with understanding, if we accept answers we can’t evaluate, ship decisions we can’t justify, and let convenience become dependence, we invite the quieter risks. intellectual degradation, brittleness, and the inability to recover when the system is wrong or unavailable. Again, go to Rashidi here: Why Intellectual Atrophy Is The Real Reason To Fear AI.

So the question becomes less “Should we use AI?” and more along the lines of:

- Where do I want to stay close to the problem, because the process matters?

- Where is the cost of being wrong high enough that I must verify, test, and slow down?

- Where can I safely let AI accelerate the tedious parts while I keep ownership of judgment?

- How do we teach kids (and teams) to treat AI as amazing, but still not a substitute for thinking?

We all have a choice. We can let our tools shape us accidentally. Or we can shape our tool use deliberately, so we get the leverage without losing the mind that makes the leverage valuable in the first place.

See Also…

- Over reliance on AI is poison to your brain.

These are a few thoughts from Allie Miller, an AI expert and someone who’s been an unapologetic booster of a great many things AI. - “writing code was never the bottleneck. Understanding it was. Still is.“

Thoughts from CTO and software architect Stephen Quick. - Thinking—Fast, Slow, and Artificial: How AI is Reshaping Human Reasoning and the Rise of Cognitive Surrender

- Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning – John Sweller

- The more that people use AI, the more likely they are to overestimate their own abilities

- ‘Don’t ask what AI can do for us, ask what it is doing to us’