This isn’t about a contest about what cohort is more or less valuable. It’s an exploration into different types of skillsets and some of what’s been going on lately with AI.

Let’s run a thought experiment about workers in general and ageism in particular. With all the talk of AI displacement, I keep wondering if there’s a less dystopian view. A lot of roles may change or vanish, but we could also see growth in niche areas. And maybe the loud claim that “we won’t need so many people” turns out to be overstated. If so, do deep skills and hard-earned judgment become more valuable, not less?

All of a sudden, some who shed too much staff, (and as is often the case, the wrong people), need to hire at least some back. Meanwhile, the nature of expertise changes such that “older” workers, wherever you want to draw that line, turn out to have a lot more value because a) the smarter machines are amazing, but turn out to still have limits, and b) AI may hollow out some early-career task bundles, and that can raise the relative value of people who can frame problems, validate outputs, and take responsibility for outcomes. I’m a huge fan of the latest AI tools and a frequent user of multiple models, several bots and agentic workflows. I’m fully buzzword compliant! And yet, in spite of the dire warnings of the viral Shumer post “Something Big Is Happening“, there may be a still be a place for talented and experienced humans. See Joe Procopio’s “It Turns Out, AI Agents Suck At Replacing White-Collar Workers” for one of many examples.

Some companies who claim they’ve cut staff thanks to AI may discover they cut too deep, losing exactly the people they really need. Meanwhile, expertise may be repriced. AI is impressive, but has limits, and it can hollow out early-career task bundles. That raises the value of people who can frame problems, validate outputs, and own outcomes. I’m a heavy user of modern AI tools and workflows, yet even with the “Something Big Is Happening” hype, there still seems to be plenty of room for talented, experienced humans See Joe Procopio’s “It Turns Out, AI Agents Suck At Replacing White-Collar Workers” for one of many examples.

Maybe this sounds naïve, but perhaps multiple cohorts will remain valuable, just in different ways. Through it’s looking to be a rocky transition. Yes, Skynet could wake up next week, but there’s also a world where things mostly work out fine. I know I’m supposed to say “if you’re not using AI in the shower, you’re doing it wrong.” I’ll work on the clickbait. For now, let’s talk about what’s actually changing.

Kids These Days

They’re often far more fluent with modern tools than we were, and they’ve grown up swimming in information; more volume, more variety, better teaching methods. But by definition, most early-career workers have limited lived experience. They may have had a few jobs in high school and college, maybe even a small side hustle, but the rest has been school, hobbies, and a first job or two.

They may also have less intuition than older cohorts did at the same age, not because they’re incapable, but because so much is abstracted away. More services handle more of life, reducing cognitive load in ways that can erode “practice-based” skills (navigation via GPS is the cliché example). Sol Rashidi calls this “Intellectual Atrophy™.” Even if that term is AI-focused, the broader pattern predates LLMs. And yet, younger workers can be astonishingly capable especially in tech while still missing some “common sense” that usually comes from scar tissue plus environment.

AI architect Jean Malaquias put it well… “senior engineers matter more in the AI era — they’re the ones who set the patterns everything else inherits.” The hard part becomes how do you become senior now, and how do you build intuition if the tools smooth over the struggle? This isn’t just about coding; as good as the tools get, the world keeps changing, and that alone creates limits.

So again the question is whether younger cohorts will build strong core skills. Today’s incentive structures reward speed and visible output, not slow fundamentals. Why take the hard route when the person next to you is accelerating with shortcuts? It was one thing to skip a slide rule once calculators existed. It’s another to skip the foundations entirely and then expect deep intuition to show up later.

Whatever You Say Boomer

A couple years ago I made a comment and got hit with an “OK Boomer.” I laughed partly because I’m GenX, partly because this guy was around my age, but mostly because it was meant as a put-down but landed as a compliment. I’ll take being accused of good work ethic and pride in craft any day. The insight for me though, was how often this move shows up now: confident dismissal of depth, nuance and accuracy in favor of weak argument, and little concern for consequences. It’s never been easier to cherry-pick support for a view, even when a bit of analysis would show it’s shaky. It reminded me of another incident where once a guy got mad at me for starting a turn on a street he was exiting. He was yelling out his window as I just calmly pointed up at the One Way sign to show him he’d gone down the wrong way on a one way street. He was too into his own broil to understand at first. His wife sitting next to him had this expression that.. well… he finally got it and then drove off. Still angry. But at least he was out of the way so I could travel down the street in the correct direction.

Is this kind of thing really a problem? Maybe so. Or worse, maybe only sometimes. Why is ‘only sometimes’ worse? Because when something works most of the time, we get complacent. And mostly that’s ok. Mostly that’s what we want. But can we recognize when we’re in a situation where that’s not ok? Where something is new or different?

I’ve noticed sometimes for younger generational cohorts, if their iCrap breaks down, they can become almost paralyzed. If this was limited to “Damn, I can’t see the train schedule” or other innocuous things, so what. Besides, these days even when things glitch, it’s usually temporary. Now it’s true enough when our phones are used as an identity or authorization credential, a glitch might be a real problem. Nevertheless, I think there’s something more insidious going on. The thought atrophy might extend to creative solutions to other simple problems as well. This is especially amazing, (although might also be partially caused by), the plethora of sources to find solutions. Personally, I love YouTube. I have a lot of hobbies and play several sports. The videos on woodworking, home DIY, light general aviation, and so much more have helped me grow and learn in so very many ways. And as I do, I add to some core base knowledge. I wonder about that base though. My base was built up not just based on “years alive,” but with hands on in specific areas within a more limited information space.

Finally, I’m approaching a point: Now that almost everything is on demand, why learn hardly anything? Do you even need much of a “base” at all? Is the time and effort to build such a thing worth it when others around you are just speeding along.

I think this is a major issue. Or at least part of it. I’m just not exactly sure as to why. More deeply intense FOMO lately? Does this even matter? I have a vague sense that it does.

Boomers At Work, See Boomers Work

I really mean both Boomers and GenX here, even though Boomers may be retiring at increasing rates. Which will also radically change everything from employee base to housing and finance. It may seem like a separate population pyramid megatrend story, but it could be related. That is, if the more experienced are needed going forward, but get tossed aside, a lot of them might not come back even if needed. Some might think, “Yes, we could use a little more financial security, but who needs to go back to the rat race.” So here’s another really funny thing about this generation and tech. When those of us maybe 40 and over were entering the work force, there were more older folks who really weren’t tech savvy and even proud of it. There were actually senior company leaders who were outright proud of the fact that they didn’t use email. I referred to such folks as arrogant d-bags. They didn’t really care much, because they were retiring soon anyway. However… and this is one big however, the reality is that a lot of us just a bit after that cohort actually built this new world of tech and online and stayed current. Not just because we had to for work, but because we like it. The kids say…

“Well, you don’t know how things are now or how they work. You’re always saying how you only had three TV channels had to be near a wired telephone to talk to someone or you’d miss a call. No email? No video of anything you wanted any time? No super low cost anywhere in the world voice communication?”

All true. Depending on specific age, we might not have had any of the new things.

So we built them.

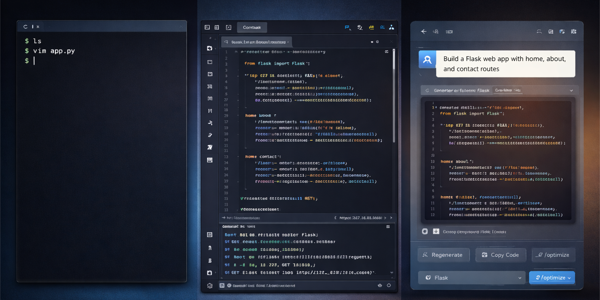

We know how they work, even the new things. From a deeper tech perspective, for those familiar, it should be downright funny that we have such advanced UI/UX now, and yet a fair amount of deep core work still gets done on a 1970s Unix shell command line of some flavor. (RIP Denis Ritchie, long live Ken Thompson, Google tech advisor in his 80s.) We also know that some of our tools, (especially some of the new ones), have dark places and sharp edges. We know that the digital threat surface area for our younger children, (all of us really), has expanded the overall risks in our world far beyond what we faced. So we know it’s not all good. We understand – more than some, but not all – this will be even more challenging to navigate, and yet meanwhile, there’s some skills that may have gotten lost along the way. Skills we still have and need to figure out how to impart, at least somewhat.

Meanwhile, it may always have been true that age discrimination has always been a thing for corporate. But it seems to have become more acute in tech, and obviously for startups. Startups might not be the same kind of golf course type culture as older school networking. At the same time, they have a vibe that’s not going to fit with many who are even into mid-career. The database guy who just moved to the ‘burbs so there’s room for kid number two isn’t going to be be hangin’ after work to drink and play foosball or whatever. Successful founders may be in their 40s or beyond, but you still typically age out of tech startups at that point, unless you’re forming your own. Unless maybe it’s in a more serious field like health or finance. Either way, we’re not talking just startups or tech, though my focus here is generally on tech and corporate.

Some of this may be changing. I’m not talking about the fact that there’s still some systems running COBOL or FORTRAN so you have to hire one of the 20 guys still alive who can help you bridge that to whatever new cloud thing you need. (Even after you’ve burned tens of millions in multiple failed projects to try to leapfrog into a modern cloud stack or whatever.) No, I’m talking about both raw skills and that more ethereal, ephemeral, more elusive idea of judgement. And pure skill as well. I know people who are in their 40s, 50s, 60s (even beyond) who can code just fine. They can write advanced SQL the way most folks can just send a Tweet. Or build business cases, go-to-market and sales plans that actually understand market needs. (Rather than generate a not necessarily solid marketing plan from AI that was based on a generated user journey map from AI that was based on data ingested some time ago and isn’t really accurate since the last model training or fine turning run, even if using some Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG).) These hand tool skills are no longer needed you say? We have power tools now; AI can do that. Maybe. Will the vibe coded AI thing really get a full data schema right for the future? Taxonomy? Ontology? Maybe. Is it solving the right kinds of problems in the first place?

How will you even know? How will you judge?

Ah, you’re going to measure some kind of performance. Great. Which thing? The thing AI told you to measure? Maybe that’s right. Or it could be overly cyclical.

Supposedly, the greatest tech risk right now appears to be for more junior coders. This makes sense. The easiest least-experience-required things to code will also be the easiest for AI to create. If there are a lot of libraries of design patterns for common functions, those might not need anyone with much skill to cobble them together for basic applications. But then, where will advanced programmers ever come from again? (Assuming we still need them of course.) A great deal of learning comes from solving increasingly more challenging problems, but to get there you have to build from a base. When that struggle is taken away, what do you do? Does everyone think they can just leapfrog past those steps? And even if some realize it’s useful to go through the hard part, what’s the motivation to take the pain when the person sitting next to you is taking the short cut? The motivation may be personal satisfaction and the endgame of some degree of mastery. Still, this could be motivationally much harder when there’s even strong incentives than there’s been to take the shortcuts.

The Nature of Dirty Jobs Work

While I’m mostly focused on tech here, it may be instructive though to also look at what’s traditionally been called blue-collar as well. Which, by the way, is increasingly deeply involved with new technology.

You’ve probably heard of Mike Rowe. He sometimes talks about the employee shortage for various categories of businesses. There’s a variety of traditional businesses that we still need – from tooling to services and so on – that suffer from the fact that there’s few younger people with skills to take them over. Many of these areas do use a lot more modern technology, yet tightly coupled with traditional and physical systems. Whether the unemployment numbers are judged as high or not, there’s millions out there looking for work. And yet we have this problem? Why? Maybe some younger workers think certain industries are sunset industries or will be automated. And yet, maybe it’s just another example of where we’re failing to maintain collective memory. Why? Do we think it’s all ok because the memory is in the machines? Do we really think we’ve imbued them with all of our knowledge; tacit, explicit and so on that we can just sit things out until we need to spin them back up?

There are small to medium sized businesses, (SMBs), all over the place that are run by folks in their 60s and 70s with no succession plans. Yet the services are still needed. Who’s going to manage this? AI alone or even with robotics isn’t going to cut it anytime soon.

In these fields, there’s going to be a lot of pressure for older workers to stay on because they’ll be getting paid more to do so. But the problem isn’t just bodies. It is that tacit and explicit knowledge transfer that goes beyond just what you can capture in a document or even a video. If you’ve ever built anything with your hands and gotten good at it, you know that at some point you just get a knack for it, a flick, a trick, something.

The Nature & Value of Intuition

Intuition comes from depth of both knowledge and experience. It’s like an AIs artificial neural network. Only actually real human “wetware” that may lack in perfect memory, but still seems to have more sensory inputs than the machines, (so far), and a creative spark that still isn’t wholly understood.

Will some kids struggle developing this because they won’t even have access to some root level primary experiences?

Let’s look at design and manufacturing prowess development as an object example. There’s a reason China has stepped up in the value chain. When you stop touching the thing, you don’t know the thing and in places where manufacturing has been conceded, there’s also a loss of higher level skills; it just lags in showing up. This isn’t a a dig on China or meant to delve into geopolitics; just to make a point about expertise. Long ago the world went for cheap manufacturing in places like China, “the world’s workshop.” Some products seem to take some kind of pride in claiming “Designed in America” or wherever. So what? I suppose that is a value. But did anyone think that the people with real live hands on product, doing actual builds, weren’t going to quickly spool up on skills and climb up the value chain? There’s old expressions about “looks good on paper” or about theory vs. practice. The reality is that reality has a lot of known unknowns and unknown unknowns. That is, random crap goes on. Things don’t quite fit. Or this or that needs a tweak here or there. So very often the learning is in the doing. Fast forward from China joining the WTO in early 2000s to now and we have more tech and knowledge transfer, design happening there and so on. (And yes, of course there’s concerns about outright intellectual property theft, but the irony here is that’s not really even necessary when you’re giving away the production line anyway.) This article is not about geo-political manufacturing rivalries. The point of this passage is just to illustrate the idea of how depth of knowledge can form through experience. And this whole transition is a great object lesson in that.

I’ve discussed Andrew Hinton’s thoughts on context before. Probably because I’m in the middle of his book now and it’s top of mind right now. My neurons’ sigmoid functions are sensitive to the ideas and since I’ve got a puny human brain with a small token context window myself, I’m just seeing context everywhere. (Or maybe because it is everywhere and I’m just helping point that out. You make the call.)

Andrew Hinton’s lens is helpful because he treats context as built. That is, a stack of cues and constraints that shape meaning and make certain actions feel “normal.” In Understanding Context, one key idea is that design doesn’t just operate inside context; it creates the conditions people think and act within. That matters in the AI era because the interface becomes part of the environment. If your work runs through a chatbot, the chatbot quietly sets defaults: what gets questioned, what gets verified, what feels “done,” and what feels like unnecessary rigor. Over time, an individual or teams can start to inherit the tool’s habits. especially around skepticism and follow-through.

And this is where embodiment comes in. Humans don’t build judgment by reading perfect answers; we build it through contact with reality. Through trying, failing, noticing what’s off, and correcting. Friction is often the signal that says, “I don’t get this yet.” If AI removes too much friction too early, it can also remove the feedback loops that form intuition. So experience won’t matter just because it contains more knowledge; it matters because it contains more context sensitivity: the ability to sense when the situation has changed, when a pattern is lying, and when the easy path is the trap. Again going to Hinton, in Understanding Context he discusses work by psychologist J.J. Gibson related to the idea of affordances. A designer might think of an affordance as a handle on a door or a selection button on a web page. Gibson might have still been forming the concept, but Hinton tries to sum it up by paraphrasing from two other psychologists, “Affordances are properties of environmental structures that provide opportunities for action to complementary organism” Hinton explains that Gibson developed his idea here as an answer about “how we seem to perceive the meaning of something as readily as we perceive its physical properties; rather than splitting these two kinds of meaning apart.”

Is this the magic part? Is this the part where we remain different than AI and maybe special? Is this something AI can never learn regardless of how many artificial neurons we give it or how many sensors? Even if so, do we still provide enough value to be worthwhile? I’d like to think so. Remember, for all my snarky sarcasm, I want to be an optimist at heart.

Now going back to Sol Rashidi, in a LinkedIn post, she explained that generative AI is a tool you used, but agentic is different in that they make choices without constant human oversight. She asked, “What does that mean for your role? Every job is a bundle of tasks. Some require your judgment, creativity, and context. Others are repetitive and routine. Agentic AI separates the two.” She goes on to explain that this “unbundling” of task types means staying relevant will be about critical thinking, problem framing, synthesis, and Knowing when NOT to use AI.

Will those lacking in depth of experience be able to make these choices well? Or will those growing up in this environment simply have new kinds of experiences better adapted to this environment. It’s hard to tell right now. The human animal is pretty simple. We seek pleasure and avoid pain. Mostly. It’s obviously not quite that simple. We aren’t driven to avoid pain so much as to avoid meaningless pain. We’ll willingly choose discomfort when it’s the price of a goal, an identity, or someone we love. Surgery hurts now to avoid worse pain later. Training hurts now to get performance, status, belonging, or health later. Pain is tolerable (even welcomed) when it’s framed as purposeful: “this is healing,” “this is progress,” “this is who I am.” I’ve been personally grappling with this hard this past year while recovering from leg surgery after a sporting accident. So I have a current and deeply embedded visceral feel for this idea right now. It’s now another pattern in my experience. You have your own. As we age, we’ll obviously have more of these experiences. (Ideally not all so painful of course!) In all cases though, they shape our perception far beyond just what can get extracted as meaning from vectorized text and other objects turned into tokens. Maybe these “older” experiences won’t always be useful in bringing to bear on new problems. Other times, this depth of experience might be essential. As always, there’s that whole context thing again.

AI’s Sources are Generally Us

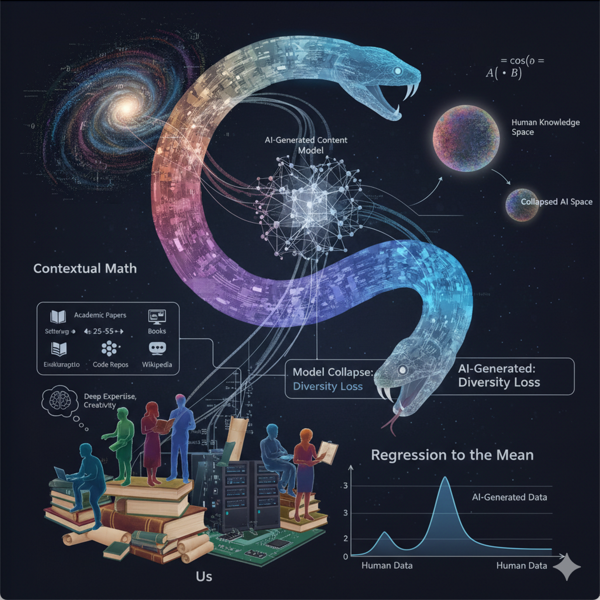

Let’s remember where all the training data for AI has come from. That would obviously be us. (Although ok, sometimes sensors as well.) But when it’s the natural language part, who specifically created all this? Where are the greatest corpora of text and other information located? It’s now fairly clear that quality training data matter. And that’s not on Twitter/X. Maybe for getting good up-to-date linguistic style that might be Reddit. But what about pure value in vertical knowledge areas? Where is all that? And who made it? Who’s continuing to make it? Let’s remember that some sources, (especially for natural language processing), might be somewhat static; books, web pages, etc. Then of course others are dynamic and growing, sensor data, health care records, and so on. For now, let’s focus on large scale natural language training data and knowledge. These are the things that really matter for interpretation. Why? Because that’s how most of the models work. Dynamic data might generate linear or logistic regression type answers. But if we’re “talking to our data” it’s generally natural language that will generate the contextual matching. (See LLM / Text Vectors for Product Managers for the math of it if you like.)

It would be really challenging to accurately determine the age of the producers of all information! But we can kind of guesstimate by proxy or make some assumptions that seem fair. If we consider that most training-relevant corpora are a mashup of books, academic papers, news / magazines, reference sources, code / docs, web pages, etc. we then ask “who produced it?” It’s not like everything comes with author age. But most of it we can probably guess is from adult, mid-career to late-career folks. Consider: Academic research: Many studies treat “average age of an academic” as ~40 (and publication productivity does not necessarily drop with seniority), Wikipedia / reference editing: Skews younger-adult, but not “all kids”, Software / open source–adjacent content: Commonly reported as concentrated in 25–34 (with smaller shares as age increases). Book authorship: Some industry summaries claim a majority of authors are 40+.

So won’t this be regression to the mean and mediocrity at scale over time? I asked an LLM about this once. The conversation is in this article Using AI for Mediocrity at Speed. But the crux of it is this: Over time, as we create more output base don AI, it gets fed back into foundational training models and other fine tuning as AIs update themselves. So they get fed back their own probabilistic output. I asked if this would result in regression to the mean. Apparently, this concern has a name. It’s either a feedback loop or model collapse, and it carries this risk because diversity and richness diminish over time. So what then?

What About Probabilistic Paths to New?

AI can traipse down many paths. It can effectively be a time machine as it considers many probabilistic outcomes. So yes, it’s conceivable AI an come up with the new by accident. We all know the story of the 10,000 monkeys typing for millions of years would randomly eventually type out Shakespeare. So maybe it’s possible there can be some new.

Will this really be the case? And even if it is, how much damage along the way as it tests things it doesn’t know is wrong? Cost damage? Property damage? Human life? I suppose, as they say, if you want to make an omelette, you’ve got to crack some eggs. Maybe that’s ok. Unless that particular egg is your particular skull.

Humans will need to not only be “in the loop” but at the beginning and ends of loops. We are making these things for us, right?

Philosophically, some believe cognition goes far beyond just the brain and its neural networks. It’s embodied and shaped by a body moving through the world, with sensation, fatigue, friction, consequence, and all the little constraints that don’t show up in a text corpus. When I’ve written about this before, I’ve referenced Andrew Hinton’s work where he treats context as a structure. So yet again, I go to his work on Understanding Context. There’s also the social aspect of things. Understanding formed through shared meaning, norms, trust, and the subtle back-and-forth of real relationships. In this view, intelligence isn’t just “having representations,” it’s being coupled to the world in a way that updates your beliefs when reality pushes back. Which is exactly what current AI often lacks. It can simulate insight without paying the price of being wrong besides losing points in some internal machine stack leader board. Humans learn because error hurts, sometimes literally. That’s why judgment is more than pattern matching. It’s knowing when the pattern is lying, or even just feeling something may be a bit off somewhere when the context is missing, and when the cost of a bad guess is unacceptable. So even if AI can stumble into novelty by exploring probabilistic paths, the question is whether it can do so with the kind of grounded restraint that comes from experienced consequence or whether we’ll still need people, with scar tissue and standards, standing between “interesting output” and real-world impact.

Ever see the movie Good Will Hunting? It’s available on Blu-ray! : ) (Blu-ray is actually interesting in itself as it may have been the last physical format war ever for consumer media.) Sean Maguire (brilliantly played by the amazing Robin Williams), the therapist, is talking to Will Hunting (Matt Damon), a genius who uses intellect and sarcasm as defence. On a park bench, Sean tells him: you can quote books and sound wise about art, love, war, and loss, but you haven’t lived those things. You haven’t traveled, loved deeply, risked heartbreak, or sat with real grief and responsibility. The point isn’t “you’re not smart.” It’s “you’re hiding.” Will’s brain keeps him safe from pain, but it also keeps him from actually experiencing life. AIs don’t experience life. This is a philosophical argument. Because soon, (in fact some already do), they may have a lot more experience than us. They can “see” into the spectrum more than humans, “hear” wider frequency ranges, gather all manner of additional sensor data. They’ll actually experience more than us. But will it matter?

Conclusion

Matt Shumer’s “Something Big Is Happening” post created quite a bit of discussion. The conversation was already happening. But his framing hit spot on target right as the pot is starting to show those little bubbles before boiling. Among the responses is one from Patrick Laughlin. In this post Something Big IS Happening. But We’re Asking the Wrong Question, he asks “what makes us fundamentally human, and why does that matter more right now than it ever has before?” He talks about how “It’s that last 20%, the core competency you actually hired someone for, where everything falls apart.”

The AI boosters seem correct in that these things are getting much better and very fast. And yet, if you work with this technology up close, there’s plenty of cracks and they seem to be getting clearer as we gain more experience. These aren’t necessarily failures. Maybe we just need to accept, (and in this case happily), that our fantastical tools which can seem to do magic really are just tools. And yet they’re still so powerful that they can automate not only much of the mundane, but somewhat more. What it’s going to take to manage them will likely be some degree of depth of intuition born of depth of experience. And that depth is usually going to be in more… oh… let’s call them “seasoned” individuals.

See Also:

- The graying of academia: will it reduce scientific productivity?

- Age and individual productivity: a literature survey

- Wikipedia:Wikipedians/Demographics

- Community Insights 2024 Report

- Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2025: Developers

- Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2024: Developer Profile

- Author demographics statistics

- Writers & Authors

- The Baby Boomer Vanishing Act: A Ticking Clock for Labour and Welfare