Note: this is about basic, issued fiat reserve backed stablecoins, not algorithmic or any other type of stablecoins.

Stablecoins are genuinely useful and increasingly foundational to crypto payments and settlement. Something to be aware of, though, is that the stablecoins most people actually use tend to be far more centralized than expected, (even if being held in your own wallet vs. a centralized exchange), with issuer and administrator controls that can freeze, pause, and sometimes effectively claw back funds, even when holders think they are holding something “cash-like.” This is not necessarily a bad thing. And actually, most typical folks would probably see the value in this. It’s just that at the same time, it doesn’t seem like this reality is discussed much, and people should know about the assets they’re holding, including whatever risks they may entail.

The reason for sharing this information and background here is just for any typical crypto user or business to understand this is a quiet structural reality that’s under-discussed outside of more technical or compliance-aware circles. The general crypto meme that often gets sold is crypto is “self-custody so no one can touch it.” Assuming you use a self-custody wallet and keep your keys safe, that’s true for bitcoin, not necessarily true for issuer-administered ERC-20s coins or tokens. The interface on most wallets make it look like cash with a simple balance. It probably feels like “If it’s in my wallet, it’s mine and nobody can touch it.” But this isn’t exactly true. The phrase “custody” often gets over-applied. For personal wallets, self-custody really means: you control the private key that can sign transactions. It does not automatically mean: the asset can’t be frozen, transfers can’t be blocked, redemption can’t be denied, or that the rules can’t change via upgrades/admin roles. With BTC, controlling the key is basically the whole story. With many stablecoins, controlling the key is only one layer.

Stablecoin Primer

Stablecoins are crypto tokens designed to hold a relatively stable price, most commonly one U.S. dollar per token. They let people move “dollars” on blockchains without taking on the volatility of assets like Bitcoin or Ethereum. The idea is they maintain a 1:1 peg.

The concept took off because crypto needed a stable unit of account for trading and settlement. Early approaches included crypto-collateralized designs and “algorithmic” experiments, and then fiat-backed models that promise redeemability for real dollars held in reserves. Over time, stablecoins expanded from an exchange convenience into something closer to modern money plumbing. They became the default quoting currency on many venues, a key building block for DeFi lending and borrowing, and a useful instrument for moving value cross-border at any hour. (See: The History of Stablecoins, Tether)

How are stablecoins minted and redeemed? from Chiara Munaretto

Calling a stablecoin a “Digital dollar” is a fair mental model, but there are some not-so-subtle differences. For starters, you’re holding a token that references a dollar claim, it’s not actually a dollar. And chances are it was issued by a company unless a country as a central bank backed stablecoin at some point. The stablecoin will still be subject to laws and compliance obligations, and also technical controls to enforce them.

Consumers hear “dollar,” and they map it to “cash.” Many stablecoins behave closer to bank money than cash. (“bank money” means the dollars that exist as ledger entries inside the banking system, not as physical cash. So they’re more like a deposit-like claim.)

Today, stablecoins function as de facto rails in parts of the global crypto economy. You can see that in at least three places:

- Trading and settlement: stablecoins are the base liquidity pair for a huge portion of spot and derivatives activity.

- DeFi: they are the “cash leg” behind borrowing, liquidity pools, and yield strategies.

- Institutional experiments: major payment networks and fintechs have explored stablecoin settlement and integration. (See: Visa Launches Stablecoin Settlement)

As of early 2026, public trackers put the stablecoin market in the low $300 billions. (See: Stablecoin market cap hits peak $311.3B) The key reality check is what sits underneath the stability. If you like, I’d written an older article on how Fiat turns into Crypto.

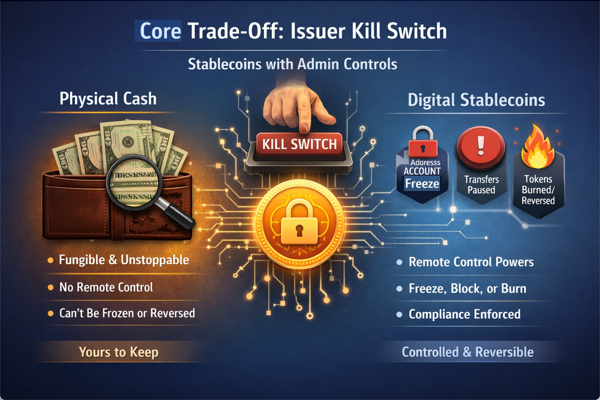

Core Trade-Off: Usually Comes With Issuer Kill Switch

Physical cash is hard to control at a distance. Once a twenty dollar bill is in your wallet, nobody can remotely pause it, freeze it, or claw it back. They can only take it by physically seizing it. It may have a serial number, but it’s still considered fungible in that who’s checking serial numbers on bills?

Most major fiat-backed stablecoins are different. They are controlled by so-called smart contracts. These token contracts commonly include administrative powers such as:

- Pausing transfers, sometimes globally.

- Freezing or blacklisting specific addresses.

- In some cases, burning and reissuing tokens in response to a lawful order or a security incident.

When this is done though, it’s usually going to be against a particular wallet, that’s associated some type of wrongdoing. It’s not about the coin itself. It is a possible that a “tainted” coin could still get seized from an innocent recipient, but this isn’t typically the case. So if a bad guy used illicit proceeds to buy a bag of gummy bears from your online candy store, that stablecoin is still going to be yours. The issuer is not generally going around “clawing back” from downstream recipients just because the payer was shady at some earlier point. However, If the sending address is already on a bad list, you might not actually be able to receive or use the funds normally. Depending on the token implementation and the wallet/exchange you use, transfers involving a blacklisted address can fail, or you can end up holding funds that are hard to move. “Taint” shows up more at off-ramps than at the token level. Even if the token contract does not mark individual coins, exchanges, payment processors, and banks often use blockchain analytics. If your deposit is linked to a flagged source, they may file reports, etc., freeze your account temporarily, require KYC/proof of source of funds, or actually reject the deposit. This should be rare, but you should be aware it’s possible.

This is often justified as compliance, consumer protection, and incident response. It is also increasingly consistent with regulatory expectations around sanctions enforcement and anti money laundering. (See: S.1582 – GENIUS Act and Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA))

None of this is automatically sinister. It can be helpful when funds are stolen or when sanctions must be enforced. But it changes what you are holding.

A large share of stablecoins are not “crypto cash.” They behave more like a digitally transferable IOU that you can self-custody, with a built-in administrative layer that can override you.

Issuer Veto In Practice: Freezing At Scale Is Not Hypothetical

The existence of controls matters less than whether they are used. And they are used.

Data analyses commonly cited in late 2025 show Tether and Circle have frozen meaningful amounts over time, with the largest stablecoin measured in the billions across multi-year windows in some datasets. (See: Tether freezes $3.3B USDT and Circle $109M USDC 2023 to 2025)

Whether you see that as law enforcement cooperation or creeping financial control, it demonstrates the underlying point: issuer and administrator roles can immobilize assets at scale, across borders, quickly. Great news for catching bad guys? Or Big Brother beyond what even Orwell imagined? You make the call.

Stable Means Target, Not Guaranteed: De-pegs Happen

Stablecoins are designed to trade near $1, not promised to stay there in every scenario. Stress reveals where the risk actually lives.

USDC in March 2023 is a clear example of reserve and banking risk showing up fast. USDC briefly traded materially below $1 after Circle disclosed that part of its reserves were held at Silicon Valley Bank as the bank failed, and markets priced uncertainty about immediate redeemability. The peg ultimately recovered, but the lesson stuck: even a regulated, fiat-backed stablecoin can de-peg when reserve custody becomes uncertain. (See: USDC Stablecoin and Crypto Market Go Haywire After Silicon Valley Bank Collapses) Everyone should kind of see the irony in this. So the punchline is basically: a “digital dollar” designed to reduce crypto volatility briefly de-pegged because of the same kind of banking-system fragility that crypto sometimes positions itself against. It’s a useful reminder that some stablecoin risk is not ‘crypto risk’ at all. It’s old-fashioned banking and liquidity risk, transmitted instantly onto blockchains. Again, irony.

TerraUSD in May 2022 is the catastrophic example. UST was an “algorithmic” stablecoin that relied on reflexive market incentives rather than robust collateral. It de-pegged and collapsed, wiping out massive value and triggering broader contagion. (See: The collapse of Terra stablecoin UST)

There is also a subtler form of de-peg risk: collateral contamination. If one widely used stablecoin wobbles and other protocols or products rely on it as collateral, liquidity, or a settlement asset, the stress can propagate quickly. (See: USDC depegs after SVB exposure)

De-pegs are not rare anomalies. They are how markets price uncertainty about reserves, redemption, liquidity, and reflexive leverage. “Reflexive leverage” in this stablecoin context means a setup where the system’s “stability” depends on market confidence, and that confidence itself is supported by prices that can fall, creating a feedback loop. It’s leverage that creates more leverage when things look good, and unwinds violently when things look bad. (In a stressed moment, markets ask: “If everyone rushes for the exit, does this thing still hold $1?” If the answer depends on selling assets into a falling market, or on a mechanism that requires fresh buyers to maintain the peg, the system becomes reflexive.)

The short answer here for the darker scenarios is that if this kind of stuff is going on, everyone is in for a bit of a rough ride and there probably won’t be many places to hide anyway. In true stress events, correlations rise and liquidity disappears, so hedges inside the same ecosystem often fail. The few places to hide in a real stress event tend to be outside crypto, and even those come with trade-offs. Correlations also tend to rise when markets get messy, so diversification is not a magic shield, but it’s still common sense. I’m not a finance professional and this isn’t advice, just an observation about how these episodes seem to play out.

A Practical Map of Ccentralization: Token-level Veto vs System-level Veto

Centralization is not binary. There are at least two layers to understand:

- Token contract controls

Does the token itself include pause, freeze, blacklist, or admin burn mechanics? - System and collateral controls

Even if the token has no simple blacklist function, can governance, collateral composition, custodians, or redemption chokepoints effectively create similar outcomes?

Fiat-backed stablecoins commonly have token contract controls because issuers need tools to comply with lawful orders and manage incidents. Some decentralized stablecoins avoid token-level blacklists, but can still inherit meaningful system-level risk through governance and collateral choices.

Two examples of nuance that matter:

- DAI: The DAI token is often described as not having a simple issuer blacklist mechanism like USDC or USDT. However, Maker governance and system architecture can still create forms of control and risk. Historically, DAI’s exposure to centralized collateral has also meant it can inherit some censorship and custody risk indirectly. (See: Maker Protocol documentation)

- Synthetic and yield-linked stablecoins: Many designs market themselves as “more decentralized,” but still have admin roles, permissioning, or compliance constraints in associated issuance, staking, or redemption flows. Claims like “no issuer veto” can be too strong once you account for the full system, not just the base token. (See: Ethena audit report)

If you want the exposé point in one line, without sensationalism: most stablecoins that behave most like dollars are dollars with administrator keys.

Other Sketchy But Real Stablecoin Issues Worth Understanding

This is not a moral judgment. It is a risk inventory. The category has real failure modes that matter more as adoption grows. And this is not to be disparaging towards stables or crypto; they have their uses. As well, it’s not like traditional banks and currencies haven’t had major issues. The goal here is to just make sure that the fast and easy to get memes aren’t obscuring some basic issues users of these currencies should understand.

- Reserve transparency is often weaker than people assume

Many issuers publish attestations rather than full audits, and reserve composition details can be incomplete or hard for typical users to interpret. Concerns about transparency and reserve composition have repeatedly surfaced in mainstream financial coverage and institutional commentary. (See: S&P downgrades its Tether rating) In other words, there’s still some trust issues that need to exist. - Redemption is not the same as price

A stablecoin can trade near $1 most of the time, but what matters in a stress event is who can redeem, how quickly, under what restrictions, and through which banking rails. Redemption is not the same as price. Stablecoins usually trade near $1 because arbitrage assumes redemptions at par are available and reliable. In stress events, what matters is who can redeem, how fast, under what restrictions, and through which banking rails. If redemption access is constrained or uncertain anywhere in the stack, the market price can slip even if the ‘$1 promise’ still exists on paper. - Banking and custody concentration risk

Even “blockchain money” frequently depends on a small set of banks, custodians, and money-market funds. That creates chokepoints and contagion pathways during crises. (See: Holding Steady: The Rise of Stablecoins) - Sanctions and illicit finance are a persistent tail risk

Stablecoins are genuinely useful for legitimate cross-border value transfer and they can be attractive for sanctions evasion and shadow payment rails. That tension drives regulatory pressure, which in turn reinforces issuer controls. (See: Sanctioned Russia adopts stablecoin shadow payments) - Yield narratives can hide leverage and counterparty exposure

When you see stablecoin yields that look too smooth or too high, risk is usually hiding in counterparty quality, liquidity mismatch, or reflexive leverage. Terra showed the extreme form, but the broader lesson applies to many “safe yield” pitches. (Once again, See: The collapse of Terra stablecoin UST)

The Non-Sensational Conclusion

Stablecoins are increasingly part of modern financial rails because they make dollars programmable, portable, and usable 24/7, and institutions have begun integrating or piloting stablecoin settlement in the real world. Even if you never hold a stablecoin directly, you may increasingly be involved in transactions where stablecoins are used in the background for settlement, treasury movement, or cross-border routing, even if the front-end experience still looks like a normal payment..

But the stablecoins that dominate real usage are often not censorship-resistant money. They are closer to regulated digital dollars with administrator controls, sometimes necessary, sometimes reassuring, and sometimes surprising if you came to crypto for self-sovereignty.

The practical takeaway is to just have basic literacy in how this all works and adjust your goals accordingly if necessary.

- If you want maximum price stability and liquidity, you are usually accepting issuer veto and reserve or custody risk.

- If you want maximum resistance to intervention, you are usually accepting more complexity, governance risk, and sometimes weaker peg performance under stress.

- If you’re holding stablecoins for value, everything is probably fine. However, just as you may want to have a couple of different bank or brokerage accounts in case there’s a problem with one of them, you may want to use multiple types of stablecoins to avoid any concentration risk of a problem.

Understanding where the control points are is important for anyone making decisions about assets they’re holding.

See Also:

- Stablecoins (AFP – The Association for Financial Professionals)

- Stablecoins: Definition, How They Work, and Types (Investopedia)

- Stablecoins Explained | FULL Guide For Beginners (YouTube)

Addendum: Chart of Some Top Stablecoins

| Stablecoin | Approx. Market Cap (Feb 2026) | Type | Has Issuer Burn/Freeze Capabilities? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USDT (Tether) | $184B | Centralized Fiat-Backed | Yes | Issuer can blacklist addresses and burn/reissue tokens for seizures; over $3B frozen in recent years. |

| USDC (Circle) | $74B | Centralized Fiat-Backed | Yes | Freezes under court orders; around $110M frozen historically, with burn capabilities for compliance. Policy |

| USDe (Ethena) | $6B | Synthetic Crypto-Backed | No | Decentralized hedging model; no central issuer veto, though staking contracts include compliance tools for sanctioned addresses. |

| DAI (MakerDAO) | $4B | Decentralized Crypto-Backed | No | Over-collateralized with no central freeze; governed by smart contracts and community votes. |

| FDUSD (First Digital) | $5B (as USD1?) | Centralized Fiat-Backed | Yes | Includes pause, freeze, and burn functions for emergencies and compliance. |

| PYUSD (PayPal) | ~$1B (smaller) | Centralized Fiat-Backed | Yes | Features pause, freeze, and burn for asset protection under regulations. |

| FRAX (Frax Finance) | ~$500M | Fractional-Algorithmic | No | Hybrid model without central issuer controls; relies on collateral and burns via protocol mechanics. |

| TUSD (TrueUSD) | ~$500M | Centralized Fiat-Backed | Yes | Issuer can freeze or burn for regulatory compliance. |